Finnish religious education: Based on one’s own religion

Finnish religious education:

Based on one’s own religion

During the last ten years, there have been vivid discussions in Finland about the nature of Religious Education and the role of religion at school in general.

This article is part of our series on the role of religion in education across Europe.

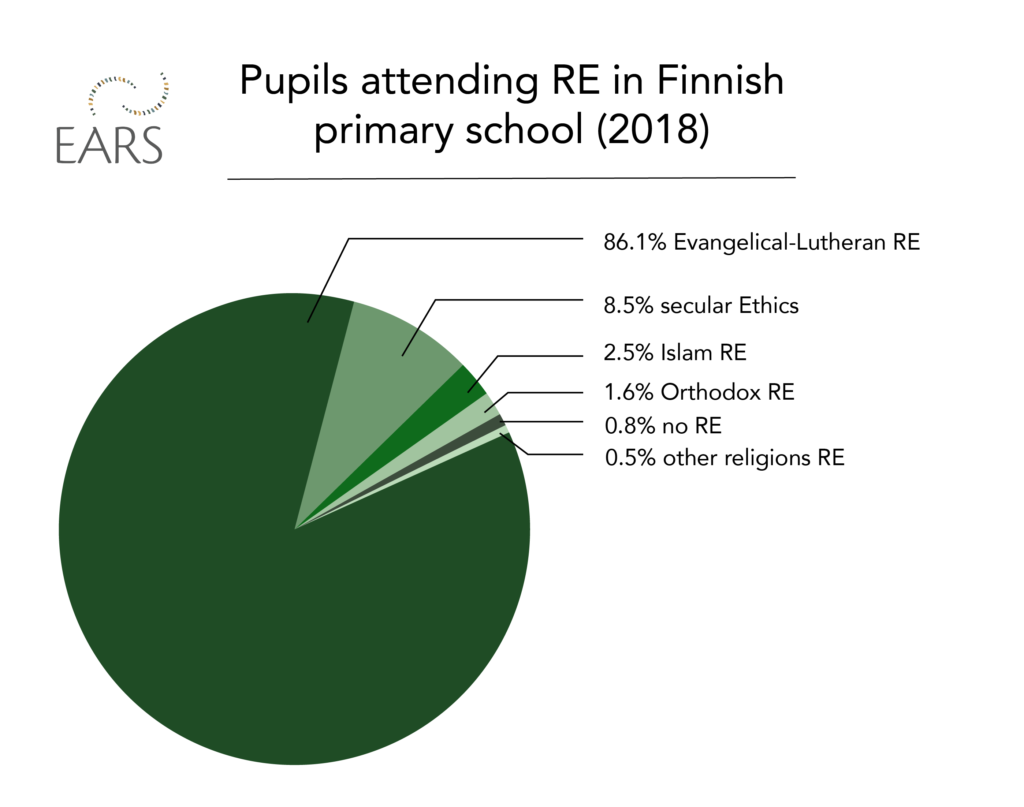

In Finland, religious education (RE) is mandatory from the age of 7 at comprehensive school (grades 1–9) and in secondary education. Pupils receive RE of their own religion, if the denomination is registered in Finland, and when there are a minimum of three pupils of the same religion in that municipality.[1] In Finland, 67.6% of the population are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church.[2] In 2018, 86.1% of pupils in primary school (grades 1–6) took part in Evangelical-Lutheran RE, 1.6% in Orthodox, 2.5% in Islam, 0.5% in other religions, 8.5% in secular Ethics, and 0.8% did not participate in RE.[3]

National curricula for RE are currently written for 13 religious groups in cooperation with the national board of education and the religious group. The Evangelical-Lutheran RE, as the majority education, is open to all pupils and students, and many non-Lutheran pupils participate in Evangelical Lutheran RE. Therefore, it is sometimes called ‘general RE’.[4]

Non-confessional teaching for all registered religious groups

RE in Finland is non-confessional.[5] This means that the contents of RE in each religion are based on that particular religion, but other religions and world views are studied as well. The aim is to give the pupil information, skills, and experiences to build their own worldview. Teachers do not have to be members of the religion they teach, but they do have to follow official university-level teacher training on the religion.[6] Pupils with no religious affiliation participate in Ethics (also called Life Stance Education), that explores ethics, culture, philosophy, and critical thinking.[7] Parents can also choose for their children not to participate in RE at school, if they receive RE at their own religious community. Jehovah’s Witnesses are the largest group that does not participate in RE at school.[8]

Private schooling is a rarity in Finland, as most children go to a municipal school. However, there are a small number of private religious schools that offer the children confessional teaching. Private schools do not have fees and they receive funding from the municipality. Most of these schools are Protestant Christian,[9] but there is also a Jewish school that has been in operation since 1918.[10] A small minority of parents homeschool their children, often due to religious reasons.[11]

In kindergarten and preschool, RE is organised differently. Worldview education aims to help children understand and respect the cultural and religious background of each child in the kindergarten group. This can be done by reflection, discussions, field trips, and celebrating the festivities of different cultures and Finnish culture.[12] However, some teachers of kindergarten and preschool are uncertain on how to execute worldview education and feel that they do not have the required training to put it to practice. Thus, worldview education in different kindergartens varies much and some kindergartens do not practice it at all.[13]

The history of RE in Finland

Historically, the first networks of schools were built and maintained by the Evangelical Lutheran church from the 17th century onwards. For a long time, Lutheranism played a strong role at public schools, even though their maintenance was given to municipalities in 1865. The Freedom of Religion Act was established in 1922, a few years after Finland gained its independence. This led to new legislation that provided RE for other than Lutheran confessions if there were twenty pupils belonging to a particular religious community. This was especially important for the Orthodox minority. The same law provided teaching of secular Ethics to pupils that did not belong to any religious community. This was the beginning of the system of separative religious education that is still in force in Finland, with some modifications.[14] The system implies the idea of democratic civil society where different faiths, beliefs, and worldviews can coexist.[15]

In spite of the seemingly pluralistic model, a vast majority of pupils have received Evangelical Lutheran RE, as Lutheranism remained the majority religious affiliation in culturally homogenous Finland until recently. Towards the end of the twentieth century, Finnish society started to become more pluralistic which put pressure on transforming the nature of RE. Following the new Freedom of Religion Act in 2003, RE was transformed to be of non-confessional nature.[16] [17]

The role of RE in modern Finnish society

As the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland has had a strong role at schools and in society as a whole, there have been many ways local congregations have cooperated with schools, such as organising events and providing spaces for school celebrations.[18] Recently, the voices that aim to wholly separate public institutions and the church have risen, also on the governmental level. For example, there have been several instances where governmental officers have limited the cooperation of local schools with the Lutheran congregations.[19] [20]

During the last ten years, there have been vivid discussions in Finland about the nature of RE and the role of religion at school in general. The separative model of RE has been criticised for separating pupils and thus maintaining the gap between religions. In part, the critique may be due to the high expenses required for educating and paying the teachers of various religions.[21] In addition, there are not enough qualified teachers of minority religions. For example, there are only 20 qualified teachers of Islam in Finland, even though there would be a need for 100 teachers.[22]

Some municipal schools have made their own decisions to start a new subject where pupils from various religions are taught together.[23] The public opinion supports such development towards a combined ‘knowledge of religions’ subject.[24] However, many RE and Ethics teachers are opposed to a general RE subject. One concern is that this would lead to more pupils dropping out of RE in school, as conservative parents would prefer their children to participate in RE organised by their own religious group. Another argument is based on studies of childhood psychological development, and states that children benefit from learning to understand and reflect first their own, inherited cultural and religious language before being able to understand different ones. Also, teachers of Ethics and minority religions fear that a general RE subject would focus too much on the Lutheran tradition, as it is still the majority religion in Finland.[25] As the subject of religion awakes strong emotions, the discussions about the future of RE are continuous, and often ideologically motivated.

For a long time, Finland has been a culturally homogenous society. Lutheranism has played a significant role which has diminished over time, along with the increase in societal secularisation. Today, the Finnish school system is a mainly secular one and the key goal of RE is understanding and tolerance between religions.

Meri Hannikainen and Pietari Hannikainen

Our team of analysts conducts research on topics relating to religion and society. In April, May and June 2021, we are focusing on the subject of education. Find out more on the EARS Dashboard.

[2] Suomalaisista kuuluu kirkkoon nyt 67,6 prosenttia – kirkosta eroaminen väheni viime vuonna selvästi

[3] Perusopetuksen 1-6 luokilla katsomusainetta opiskelleet

[4] Religious Education in Finland

[6] Opetusta sääteleviä lainkohtia

[8] Eri uskontojen ja elämänkatsomustiedon opettajat vastustavat yhteistä katsomusainetta

[9] Kristillisten koulujen ja päiväkotien liitto ry – Etusivu

[10] Kampissa toimii juutalainen koulu, jonka historia on poikkeuksellinen koko Euroopassa

[11] Kotiopetus valitaan usein uskonnollisista syistä

[12] Päiväkodissa katsomuskasvatus on kaikille lapsille yhteistä

[13] Varhaiskasvattajien näkemyksiä katsomuskasvatuksen toteuttamisesta, yhteistyöstä ja osaamisen kehittämisestä

[14] Religious Education in Finland | Temenos – Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion

[15] Religious Education in Finnish School System

[16] Bruce, Steve 1996. Religion in the Modern World: From Cathedrals to Cults. Oxford: Oxford University Press

[17] Ubani Martin; Rissanen, Inkeri & Poulter, Saila 2019. Contextualising dialogue, secularisation and pluralism. Religion in Finnish public education. Münster: Waxmann

[18] Kirkko ja uskonto koulussa – evl.fi

[19] Apulaisoikeusasiamies linjasi: Koulun yhteisen joulujuhlan järjestäminen kirkossa on lainvastaista – “Kirkko on nimenomaan jumalanpalvelusten toimittamiseen tarkoitettu paikka”

[20] Kulttuuriperintöä vai uskonnon harjoittamista? Koulut vetävät joulujuhlat uusiksi pikaisella aikataululla, sillä niitä ei saa järjestää kirkossa

[21] Uskonnon yhteisopetus kiinnostaa – islamin opettajilta tyrmäys

[22] Suomessa on kova pula pätevistä islaminopettajista – Uutiset

[23] Moni koulu opettaa jo eri uskontoja samassa luokassa – Laki kuitenkin erottelee luterilaiset, ortodoksit, muslimit, katolilaiset ja ET:n opiskelijat

[24] Suurin osa suomalaisista muuttaisi koulujen uskonnonopetusta – elämänkatsomustiedon opettaja: “Uskonto sanana voi olla jollekulle iso peikko”

[25] Eri uskontojen ja elämänkatsomustiedon opettajat vastustavat yhteistä katsomusainetta