Navigating religious freedoms within a secularising society

Navigating religious freedoms within a secularising society

Given the growing lack of religious affiliation in the UK, normativity has become increasingly more secular and political. This has led to clashes between the government and religious institutions.

This article is part of our series on normativity in Europe.

Religious identity within the United Kingdom

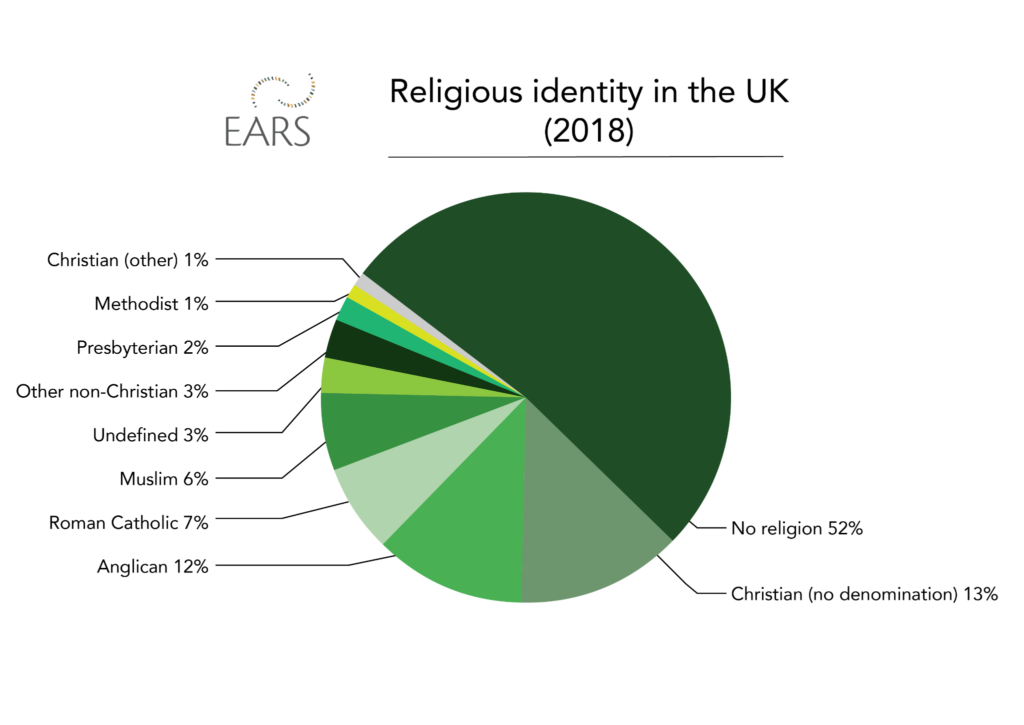

The United Kingdom (UK) differs from many of its European peers as it is one of the few nations to have a state religion, Anglicanism.[1] Despite the established status of the Church of England, the vast majority of the British populace do not consider themselves members. In fact, studies suggest around as little as 12% of the British population identify as Anglican.[2] Overall, 38-59% of Brits identify as some denomination of Christianity, whereas 25-52% profess no religion at all.[3] [4]

Additionally, some argue that ‘identifying’ as one religion differs from actual religious participation. If statistics on regular church attendance are examined, the numbers drop further, with reports of about 5% of the British population attending church in 2015.[5] [6] For comparison’s sake, the third-largest religious identification, besides Christian and ‘no religion’, is Muslim, with around 5% of the population identifying thusly in 2011.[7]

Scottish hate crime bill controversy

Given the growing lack of religious affiliation in the UK, normativity has become increasingly more secular and political. This has led, in some situations, to clashes between the government and religious institutions.

One such struggle recently arose in the form of Scotland’s Hate Crime and Public Order Bill. The bill, designed to modernise Scotland’s hate crime laws, would scrap unnecessary laws, such as antiquated rules that criminalised blasphemy.[8] Other components, however, created new measures for handling hate speech, which swiftly generated controversy over freedom of speech and religion. One section of the bill would have penalised the possession of “threatening, abusive, or insulting material with a view to communicating the material to another person.”[9] Another would have criminalised “stirring up hatred,” regardless of authorial or speaker intent, thereby placing restrictions on inflammatory material.[10]

A widespread coalition from groups like the National Secular Society and the Network of Sikh Organisations criticised the law.[11] The Catholic Church warned that those who opposed gay marriage or increased transgender rights on religious grounds could be prosecuted.[12] [13] The Bishops’ Conference of Scotland feared that the restrictions on inflammatory writings could be interpreted to cover religious texts, like the Bible.[14]

Not all groups united in opposition, though. Muslim Engagement and Development and the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities (SCoJeC) agreed with the Scottish government asserting that, despite imperfections, the bill ought to be passed. Acknowledging some of the aforementioned concerns, SCoJeC called for increased protections for religious beliefs, noting that some religious communities, like Jews and Sikhs, would be covered under ethnic protections, but that such protections should extend to members of all religions.[15] [16] [17]

Ultimately, several of the controversial elements were removed from the bill by the time it passed into law in March 2021.[18] That said, concerns, particularly around freedom of expression, still exist. The debate over the bill illustrates the delicate balance in the UK amongst freedom of expression, religious beliefs, and ethnic and religious minorities, an area likely to see continued debate in the years to come.

Gay conversation therapy controversy

A good illustration of the tension surrounding normativity in the UK has been the practice of so-called ‘gay conversion therapy’. Such ‘therapy’ is aimed at people who exhibit sexual attraction towards members of their own sex, and seeks to change them to a heterosexual orientation.[19] ‘Treatment’ often involves a combination of psychological, spiritual, and physical interventions.[20]

A 2018 survey of LGBTQ+ people in Britain found that conversion therapy is most commonly offered by some faith communities, and is usually based upon theological reasoning.[21] Gay conversion therapy is often justified by asserting that homosexual tendencies arise because of sinful desires or due to the influence of Satan. Homosexuality is therefore seen as an illusion, a (temporary) distortion of one’s true human nature.[22] Conservative brands of many religions have historically understood sex to be legitimate only as a means for procreation, and therefore consider gay sex to be illegitimate.[23]

The LGBTQ+ community, medical practitioners, and human rights advocates all condemn the practice. According to them, it is a breach of the individual’s right to self-determination and leads to a host of negative health impacts.[24] It also relies upon the premise that it is normative to engage in sexual activity only with those of the opposite sex.

However, some say that the right to religious freedom is being compromised by a left-wing neo-liberal ideology that wishes to impose its own normative secular values upon everyone.[25] A ban on conversion therapy would be discriminatory to faith communities and may lead to the practice being forced underground.[26]

So far, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government has been slow to deliver the promised ban on conversion therapy.[27] Part of the bind he finds himself in is due to competing (and so far irreconcilable) normativities.

A dangerous bargain? State-funded and -regulated faith schools

Normativity in education is an inescapable phenomenon as much as normativity in funding and legal requirements. The UK has ‘faith schools’ that receive funding from the state. These schools sit at the intersection of several forms of normativity.

While ‘faith schools’ are often lumped together, they represent many different communities. In 2014, in England, among the 6,210 state-funded faith primary schools, 70.77% were affiliated with the Church of England, 26.45% Roman Catholic, 0.58% Jewish, 0.14% Muslim, and 0.08% Sikh. Among the 628 state-funded faith secondary schools, 33.54% are Church of England, 50.78% Roman Catholic, 1.88% Jewish, 1.41% Muslim, and 0.47% Sikh.[28] The imbalance may constitute a kind of normativity: Christian predominance. However, a withdrawal of support for faith schools would affect not only Christian schools, but disproportionately religious minority schools.

Education is a form of cultural normativity, determining what is taught, how it is taught, and to whom it is taught. All state-funded – including non-faith – schools legally must offer religious education of some kind, though students’ participation is non-obligatory.[29] State-funded faith schools have more control over curriculum, but funds can influence what can be taught and how.

The level of legal normativity enforced on faith schools varies with their types, from significant control in ‘voluntary controlled schools’ (most control is ceded to the local council) to very little in ‘academies’ (they charge no fees but operate virtually independently).[30] [31] [32] [33]

The most controversy surrounds social capital’s normativity, i.e. who can go to faith schools. Faith schools can choose students on the basis of their family’s religious affiliation and participation, though not all do.[34] [35] Yet social normativity is also involved with questions of who gets to run the school, with regulations requiring faith schools to surrender some autonomy in governance to get funds.[36] [37]

Faith schools demonstrate rival normativities. Yet, the diversity of school types and local situations affect which normativity takes precedence. Both religion and the state could be said to have made a dangerous bargain: religion for letting the government meddle in their education, or the government for letting religion do the same.

Learning from these case studies in UK normativity

The religious and political landscape of the UK is diverse. Complex religious and non-religious normativities present within UK society are compounded by the UK’s several devolved legislatures.

All societies must implement normativities, but normativities at the intersection of religious and political life have the potential to be weaponised in either direction. Perhaps in the above cases, these rival normativities will not be reconcilable. However, they show that the first step forward is for communities holding rival normativities to seek to remove causes for fear of one another and increase causes for trust.

Tyler Mikulis, Frazer MacDiarmid and R. Anthony Buck

Our team of analysts conducts research on topics relating to religion and society. In the second half of 2021, we are focusing on the subject of normativity. Find out more on the EARS Dashboard.

Sources

[1] Four-in-ten countries have official state religions or preferred religions

[2] British Social Attitudes: The 36th Report, London: The National Centre for Social Research

[3] The exact number differs between the slightly outdated 2011 census and the 2018 British Social Attitudes report: British Social Attitudes: The 36th Report, London: The National Centre for Social Research

[4] United Kingdom – England Population: Demographic Situation, Languages and Religions

[6] Church Attendance in Britain 1980-2015

[7] United Kingdom – England Population: Demographic Situation, Languages and Religions

[8] Why is Scotland’s Hate Crime Bill so controversial?

[9] Why is Scotland’s Hate Crime Bill so controversial?

[10] Why is Scotland’s Hate Crime Bill so controversial?

[11] Bibles and newspapers ‘would be banned under new hate crime law’

[12] Why is Scotland’s Hate Crime Bill so controversial?

[13] Bibles and newspapers ‘would be banned under new hate crime law’

[14] Bibles and newspapers ‘would be banned under new hate crime law’

[15] Bibles and newspapers ‘would be banned under new hate crime law’

[16] Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Bill Response from the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities

[17] Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Bill Submission from Muslim Engagement and Development

[18] MSPs approve Scotland’s controversial hate crime law

[19] What is conversion therapy and when will it be banned?

[20] Inside the gay ‘cure’ church offering ‘dangerous’ starvation therapy

[21] National LGBT Survey: Research Report

[22] Stances of Faiths on LGBTQ Issues: Southern Baptist Convention

[23] Why the ban on conversion therapy has to include religious groups

[24] The Lies and Dangers of Efforts to Change Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity

[25] We don’t need a new law against ‘conversion therapy’

[26] Religious group warns against LGBT+ conversion therapy ban

[27] Anger as ban on LGBT conversion therapy is mired in ‘loophole’ and fresh delay

[28] Church schools move towards open door selection

[29] The national curriculum: Other compulsory subjects

[30] Types of school: Faith schools

[31] Types of school: Academies

[32] Church of England ‘Church schools and academies’

[33] Types of school and governing status

[34] Church schools move towards open door selection