Addressing normativity in Religious Education

Addressing normativity in Religious Education

Religious Education (RE) can be a meaningful tool to promote understanding among religions in a pluralistic society.

This article is part of our series on normativity in Europe.

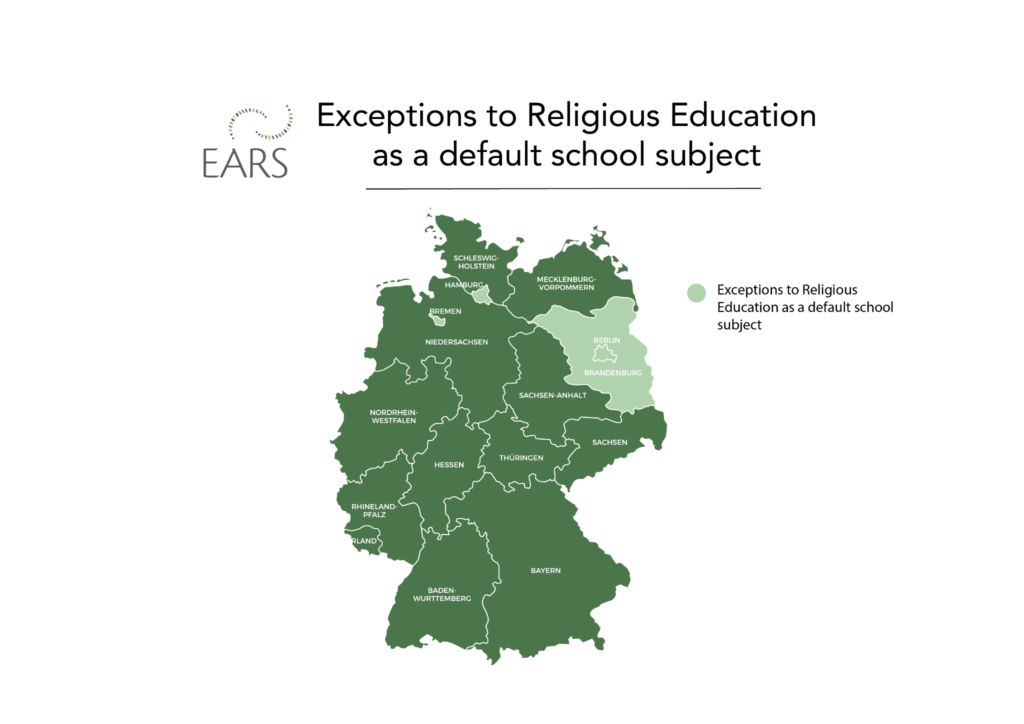

In Germany, denominational Religious Education (RE) as a school subject is the default option in 12 out of 16 federal states, except in Berlin, Brandenburg, Bremen, and Hamburg.[1] Despite its legal status in the German Basic Law, this organisational form of RE finds itself increasingly under pressure in public discourse.[2]

The normative character of RE

According to religious educators, RE should not only impart religious knowledge and insights, but also stimulate students to engage with religious approaches critically. Accordingly, students and teaching staff should be aware of and be able to deal with the normative implications of religion and religious education. They should also bring them into critical dialogue with faith and theological practices in the here and now.[3]

In other words, the goal of RE includes two kinds of competencies: the ability to communicate religiously (to participate in a religion), and the ability to communicate about religion (to observe religion). Religious educators like Prof. Bernhard Dressler from the University of Marburg and Prof. Godwin Lämmermann from the University of Augsburg also emphasise the normative aspect of RE by providing knowledge and orientation about religion. It questions the validity of religious practice.[4]

Normativity as an argument against RE today

However, in an increasingly secular society, denominational RE, the most common kind of RE in Germany, is losing social support. In Germany, many people see religion as a private matter that should not be taught publicly, especially in state schools. The number of members of religious institutions is also declining.[5] In addition, state-funded RE at schools is perceived as a sign of state-church cooperation that is no longer in accordance with the image of a modern democratic society.[6] The changing demography in Germany is also shaping the development of RE. While the Protestant and Catholic churches are losing members at a significant rate, the number of Muslims and people without religious affiliations is on the rise.[7] This religious heterogeneity makes RE harder at an organisational level.[8]

On the other hand, how to deal with religious plurality and diversity, fairly and without prejudices, is becoming one of the greatest challenges in today’s Germany. Some argue that RE, particularly confessional RE, prescribes a certain worldview or confessionally-oriented ideology to students and does not comply with Germany’s pedagogical standards and social requirements.[9] [10] For example, the alleged creationist position in biology classes at Hessen’s schools has caused heated public discourse and given rise to serious doubts about the educational value of RE.[11] However, according to Prof. Bernhard Dressler, the fact that the majority of those involved have protested against this approach shows the necessity of religious competence.[12]

Religious educators call for RE

The ideological critique of RE is nevertheless directed against the normative perspective of RE itself. In Germany, RE has integrated theories and concepts from neighbouring related fields of study varying from theology, pedagogy, and sociology. It ensures an innovative and critical approach to the existing discourse on RE. In doing so, RE is asked to reflect on itself and its own theory formation.[13]

Whilst these actions against denominational RE are largely to be seen as part of a secularising and democratic process, they fail to prove themselves as free from normative implications. For example, Prof. Andrea Lehner-Hartmann from the University of Vienna has rejected the polemical distinction between the ‘ideology-suspicious’ RE and the ‘value-neutral’ Moral Education. According to religious educators, the very task of education is to make pupils aware of different worldviews and facilitate dialogues between them. Only this enables democratic coexistence. Both Moral Education and RE must contribute to this competence, neither in a neutral or value-free way nor in an ideological way. [14]

Research also shows that the so-called ‘neutral’ Moral Education does not have much support among German headteachers, who often prefer integrative RE over the cooperative ‘religion for all’.[15] On the other hand, some pedagogues suggest that confessional RE helps to form a religious identity, arguing that students or parents always have the right to withdraw from RE and can attend Moral Education or other substitute classes.[16] What is more, RE makes it possible to provide access to religion and deal with religion as a cultural phenomenon in which an individual faith can be communicated in the social sphere. [17]

Bridging bubbles: normativity as a tool to promote religious plurality

For some, the normative implications of RE are no longer compatible with the concept of the modern secular state and cultural diversity. With RE being the only subject in Germany’s school system which is not fully regulated by the state, it is clear that this normative character of RE is approved by the state, if not supported.[18] The attempt to ‘promote’ religious and cultural diversity by pushing religion and religious discussions out of the public sphere, is thus expected to become a contradiction in itself.

Religious educators argue that this exact character is what makes RE educationally valuable. Rolf Schieder, Professor of Protestant Theology, speaks of the theological and social values of religious education: “State-organised religious education makes an essential contribution to the civilisation of religious life. It prevents religion from fundamentalism. At the same time, it can also strengthen a society’s awareness of its own religious-cultural roots.”[19]

To conclude, RE seeks to create religious competence: the competence to participate in a religion as an individual and to communicate about religion as a part of society. By enabling pupils to reflect on its own normative implications, RE’s normative character could be a meaningful tool to promote understanding among religions and social integration in a pluralistic society.[20] [21]

Our team of analysts conducts research on topics relating to religion and society. In the second half of 2021, we are focusing on the subject of normativity. Find out more on the EARS Dashboard.

Sources

[1] German principals’ attitude towards the form of religious education at state schools

[2] Coping with diversity in Religious Education in Germany

[3] How to Work with Normativity in the Religious Education Faculty/Program?

[4] Das Wissenschaftlich-Religionspädagogische Lexikon im Internet

[5] Gärtner, C. (2015). Religionsunterricht-ein Auslaufmodell? Begründungen und Grundlagen religiöser Bildung in der Schule [Religious education at its end?]. Paderborn: Schöningh.

[6] Problem ist fehlende Trennung von Religion und Staat – Leserbriefe

[7] Religionszugehörigkeiten 2019

[8] German principals’ attitude towards the form of religious education at state schools

[9] Religionsunterricht: Lehren sollt ihr, nicht bekehren | ZEIT ONLINE

[10] Coping with diversity in Religious Education in Germany

[11] Hessische Schulen: “Kultusministerin fällt auf Kreationisten herein”

[12] Feindt, A., Elsenbast, V., Schreiner, P., & Schöll, A. (Eds.). (2009). Kompetenzorientierung im Religionsunterricht. Befunde und Perspektiven. Waxmann Verlag.

[13] Das Wissenschaftlich-Religionspädagogische Lexikon im Internet

[14] Religions- und Ethikunterricht “nicht wertneutral”

[15] German principals’ attitude towards the form of religious education at state schools

[16] Debatte um Abschaffung des Religionsunterrichts in Rheinland-Pfalz | DOMRADIO.DE

[17] Feindt, A., Elsenbast, V., Schreiner, P., & Schöll, A. (Eds.). (2009). Kompetenzorientierung im Religionsunterricht. Befunde und Perspektiven. Waxmann Verlag.

[18] Coping with diversity in Religious Education in Germany

[19] Theologische Fakultäten – reformbedürftig, aber notwendig :: Institut für Religion und Politik

[20] Feindt, A., Elsenbast, V., Schreiner, P., & Schöll, A. (Eds.). (2009). Kompetenzorientierung im Religionsunterricht. Befunde und Perspektiven. Waxmann Verlag.