Balanced religious education at Portuguese public schools

Balanced religious education at Portuguese public schools

Portugal still has a strong link between religion and education. However, in recent years, there has been a discussion on the need to create a more inclusive and transversal school subject.

This article is part of our series on the role of religion in education across Europe.

Religious education at public schools

In Portugal, religious education (RE) at school is neither mandatory nor forbidden. Portugal is a non-confessional state, meaning that State and Church are formally separated. Therefore, RE is not confessional.[1] The Portuguese Constitution of 1976 ensures the freedom to learn and to teach[2] and also guarantees that this freedom is extended to all private schools.[3] As established in the Portuguese Act on Religious Freedom, ‘[m]oral and religious education classes in public schools are optional and not an alternative to any curriculum area or subject’.[4]

State, religion, and religious freedom

According to the Act mentioned above, churches and other religious communities are free to carry out their religious activities without interference from the State or third parties.[5] Pupils under 16 years of age wishing to attend classes on RE must express this wish through their parents.[6] RE programmes, teacher training, and class materials must be provided by the religious communities.[7] However, for these classes to run, a minimum number of pupils must attend. This means that teaching of a particular religion may be impacted based on the higher or lower prevalence of a religion among the population.[8] On the other hand, for Catholic RE, the training and recruitment of teachers, as well as the elaboration of the programmes, are paid for by the state.[9] Therefore, the Portuguese State assumes as its obligation the task of religious denominations, which contradicts its laicity and the principle of separation between Church and State. In practice, the principle of equal treatment of the different religious denominations is also not observed.[10]

Religious communities…

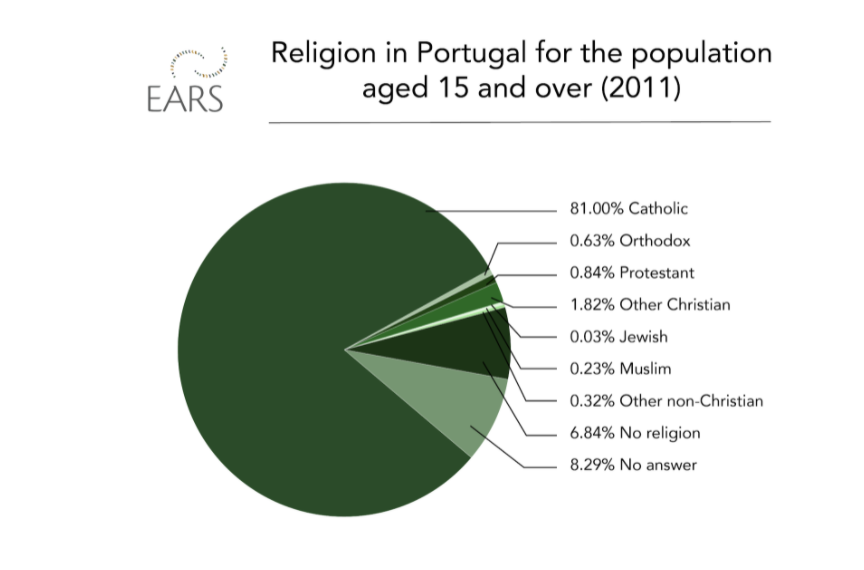

According to the last Portuguese population census held in 2011,[11] the majority of Portuguese people identify as Roman Catholic (81%), though only about 19% practice their faith and go to Mass regularly.[12] Nevertheless, there are also many other religions, mainly due to the migratory flows that have occurred since the 1970s. Among the other religious communities, the following stand out: Orthodox, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, and Evangelicals, formed almost entirely by immigrants and their families.[13]

However, the most recent Catholic Church statistics released by the Bishops’ Conference, from 2014, put the percentage of Portuguese who call themselves Catholic at 77.03%. At the same time, there is an increase in the number of those who profess other religions and those with no religion.[14] According to Alfredo Teixeira, Associate Professor at the Theology Faculty of the Catholic University of Portugal, this trend continues to this day.[15]

…and religious education

Besides the Catholic Church, only three more religions exercise the right to provide RE in public schools: the Aliança Evangélica Portuguesa,[16] the Bahá’í,[17] and the Buddhist[18] communities based in Portugal.

Nevertheless, for André Folque,[19] a member of the Commission on Religious Freedom, as RE in public schools is optional, there is “a significant gap in the [Portuguese] educational system” when it comes to teaching and learning about religion in general. That is why Portuguese researcher Fernando Catarino says that RE in Portuguese public schools remains almost exclusively Catholic and claims that there is a lack of a subject that addresses religion in a “cross-cutting and balanced” way.[20]

The link between religion and public school

In the Portuguese case, as is the case for other European countries with a close connection between the Roman Catholic Church and national culture, there is still a strong link between religion and education. However, in recent years, there has been a discussion on the need to create a more inclusive and transversal subject at school. For some political parties, removing the subject of Catholic RE from public schools is one of the goals, not least because in May 2018, there were more non-practicing Catholics (48%) than practicing Catholics (35%) in Portugal.[21] Rather than asking what link there might be between religion and public school, José Brissos-Lino, Doctorate in Psychology and Specialist in the Science of Religions, proposes a reflection on what school is for. As suggested by him, if schools really want to prepare pupils for life, they should replace classes on RE of religious denominations with a subject on ‘Introduction to Religions and Spiritualities’. Such a subject would deal with the religious phenomenon, without forgetting the agnostic and atheist perspectives.[22]

Our team of analysts conducts research on topics relating to religion and society. In April, May and June 2021, we are focusing on the subject of education. Find out more on the EARS Dashboard.

[1] Constitution of the Portuguese Republic. VII Constitutional Revision. Part I – Fundamental rights and duties. Title II – Rights, freedoms and guarantees. Chapter I – Personal rights, freedoms and guarantees. Article 41 – Freedom of conscience, religion and worship, No. 4. Churches and other religious communities are separate from the State and are free in their organisation and in the exercise of their functions and worship. [and] Article 43 – Freedom to learn and teach, No. 3. Public education shall not be confessional. Constituição da República Portuguesa

[2] Constitution of the Portuguese Republic. VII Constitutional Revision. Part I – Fundamental rights and duties. Title II – Rights, freedoms and guarantees. Chapter I – Personal rights, freedoms and guarantees. Article 43 – Freedom to learn and teach, No. 1. Freedom to learn and teach is guaranteed. Constituição da República Portuguesa

[3] Constitution of the Portuguese Republic. VII Constitutional Revision. Part I – Fundamental rights and duties. Title II – Rights, freedoms and guarantees. Chapter I – Personal rights, freedoms and guarantees. Article 43.º – Freedom to learn and teach N.º 4. The right to establish private and cooperative schools is guaranteed. Constituição da República Portuguesa

[4] Portuguese Act on Religious Freedom. Law No. 16/2001. Official Gazette No. 143/2001, Series I-A of 2001-06-22, Article 24 – Religious education at public schools, No. 2. Lei da Liberdade Religiosa

[5] Portuguese Act on Religious Freedom. Law No. 16/2001. Official Gazette No. 143/2001, Series I-A of 2001-06-22, Article 23 – Freedom to practice religion and worship. Lei da Liberdade Religiosa

[6] Portuguese Act on Religious Freedom. Law No. 16/2001. Official Gazette No. 143/2001, Series I-A of 2001-06-22, Article 23 – Freedom to practice religion and worship, subparagraphs c) «To teach in the manner and by the persons authorised by themselves the doctrine of the religious faith they profess»; h) «Appointing and training its ministers»; and, i) «To establish seminaries or any other establishments of religious training or culture». Lei da Liberdade Religiosa

[7] Portuguese Act on Religious Freedom. Law No. 16/2001. Official Gazette No. 143/2001, Series I-A of 2001-06-22, Article 24 – Religious education at public schools, No. 5. «The churches and other religious communities shall be responsible for training teachers, preparing programmes and approving teaching materials, in accordance with the general guidelines of the education system». Lei da Liberdade Religiosa

[8] A Educação Moral e Religiosa num país em processo de descatolicização: as representações programáticas dos profe

[9] Decreto-Lei 70/2013, 2013-05-23

[10] Religião e Moral nas Escolas, um processo de fidelização

[11] Portal do INE. The next census of the Portuguese population will take place in 2021.

[12] Teixeira, A. (2012). Identidades religiosas em Portugal: representações, valores e práticas. Centro de Estudos e Sondagens de Opinião & Centro de Estudos de Religiões e Culturas – Universidade Católica Portuguesa.

[14] Em que acreditam os portugueses?

[15] Em que acreditam os portugueses?

[17] A Fé Bahá’í – Website da comunidade mundial bahá’í. Curiosity: A well-known figure of the Bahá’í Community is the Olympic champion Nelson Évora.

[18] União Budista Portuguesa – União Budista Portuguesa

[19] André Folque has been a member of the Commission on Religious Freedom since 2003. André Folque, «Religion in public Portuguese education», in Gerhard Robbers (Ed.), Religion in Public Education – La religion dans l’éducation publique, European Consortium for Church and State Research, Trier, 2012, pp. 399-424.

[20] Portugal não tem um ensino religioso “equilibrado” e “transversal”

[21] Livre quer retirar Educação Moral e Religiosa da escola pública

[22] Visão | O que tem a religião a ver com a escola pública?