On the eve of other times

On the eve of other times

Look around European society in 2024, and you’ll see two forces that seem contradictory but fit together perfectly. Forces that, like a shadow, sketch the outline of a society where notions such as justice, equality, and respect no longer seem to matter. Instead, these values, along with the religions they stem from, appear to have become extinct species. The dodos of morality, the dodos of the humanities. Soon, only winners and losers will matter, and self-interest will reign supreme, with the rule of the day being: “the winner takes it all.”

The drive for innovation

What forces are these? Innovation and renewal on the one hand versus conservatism and right-wing extremism on the other. To start with the first, there is an enormous drive for innovation, which is mainly felt in the field of economics and sciences. AI is the best example of this and is also a good example of the combination with the other trend, pronounced conservatism, as it is often developed within and utilized by systems that reinforce hierarchical structures and control mechanisms. The growth of the American economy continues thanks to far-reaching innovation and the role of high-tech companies is increasing. Think in particular of the Magnificent Seven (the seven most important tech companies including e.g. Microsoft, Apple, Meta). For example, the value of the Nvidia share rose by almost 200% in 2024 and the Tesla share rose by 42% in one month, up to November 14. The Draghi report therefore strongly warned that Europe has absolutely insufficient competitiveness. So how do we prevent Europe from becoming an economic museum? That is one force, enormous innovation that immediately translates into economic power.

The pull of conservatism

The other side, social development, demonstrates an enormous tendency towards conservatism and the increasing need to live among equals. ‘Equals’ no longer mean equal as in the equality of people as formulated by the French Revolution, but equal in the sense of white people, male, raised in a Jewish-Christian culture, and in possession of the correct nationality. It is a conservatism that divides people into groups of us and them, and they are of course less valuable than we are. Because it is all about identity and the policy derived from it, it is a conservatism, based on nationalism and gender inequality, among other things, that divides people into groups where one group is deemed less valuable than the other. Values such as nationalism are thereby exaggerated so that they can create enemy images: the fear of a chaotic, uncertain future contrasted with an idealized vision of a perfect, stable past. These fictitious enemy images are then justified in the fact that any doubt about their truth is considered a betrayal of one’s own nation, one’s own people. Our own people come first and last.

A paradox: how these forces coexist

In this way, we live in an opposing force field. On the one hand, innovation, creativity and development, on the other hand, conservatism, the need to build walls and not renew society but return it to a dreamed past. The strange thing, however, is that these two tendencies can fit together seamlessly. Reactionary and autocratic societies such as the US and China appear to be able to shape political and moral conservatism in such a way that open spaces are created, outside the social playing field, for highly technological research. These technological developments can then be used to track down opponents or to create a fanatical following based on disinformation or algorithms. Fascinating developments. Because although it is far from necessary, both developments seem to reinforce each other.

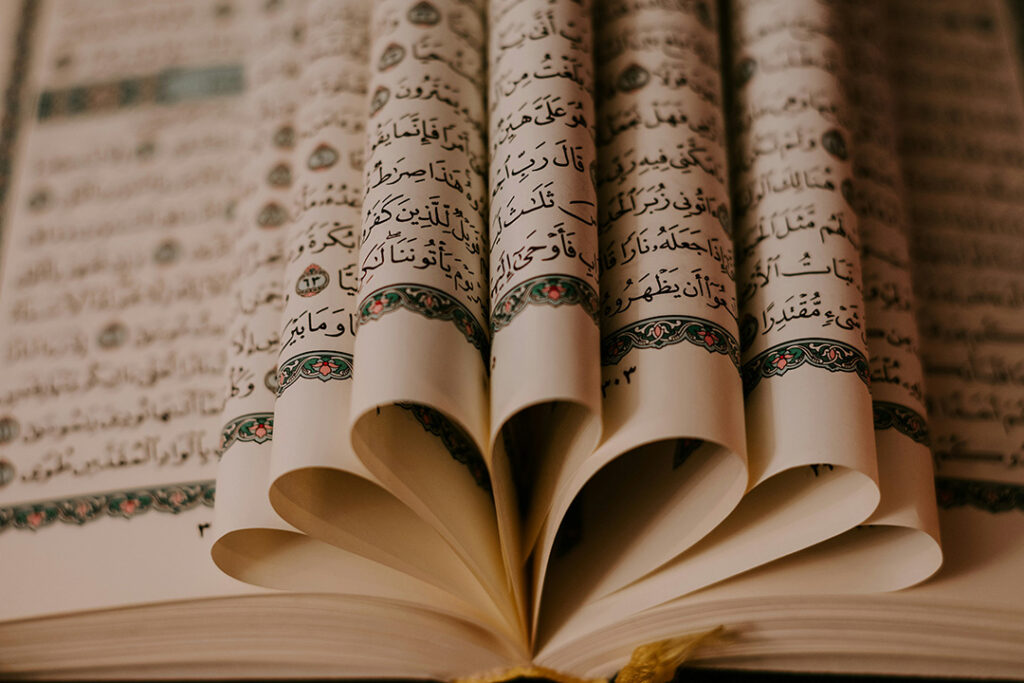

Studying religion amid contradictions

In that global force field in which almost all developments can also be translated into a geopolitical game, what are religious studies and theology doing there? Of course, technological development like the creation and use of AI has long since entered these disciplines. On the other hand, the growing conservatism within religions is studied, the tendency towards orthodoxy, and the many ways in which modern popular movements within Christianity strip that same Christianity of its pluralism and stratification.

The innovation within theology and religious studies

But are those disciplines themselves also innovative? Just as in patristics the church fathers dared to forge philosophical concepts into new forms and thus made the transition from narrative (the stories about Jesus) to conceptual level possible. Or as in the Middle Ages theologians dared to apply logic to theology, and great conceptual innovations took place again. Or as when Schleiermacher gave theology a new basis after Kant had stated that it did not belong in the university. Do our disciplines now provide new concepts to give words to the recently discovered reality that lies between the human and the artificial? To perhaps approach the human self differently?

It is conceivable that the major conflict areas in our society — democracy, armed conflict, body — are precisely the areas in which these new concepts should be developed. Classical democracy, for example, is undermined in many ways but is now also based (certainly not exclusively!) on specific Christian concepts, for example, the equality of people before God and gender equality. Elements that Christianity itself has unfortunately taken liberties with for centuries (women who, according to tradition, cannot fulfil the same roles as men), but that innovation potential is of course, there.

A legacy of conservatism

A caveat is appropriate here. Church developments almost always have lagged behind social developments and followed them only reluctantly. Every aggiornamento could only be achieved at the cost of much struggle. In recent times, this was compounded by the fact that churches, or their office bearers, had violated the physical integrity of many of their believers in an unheard-of way. In other words, in practice over many centuries, church tradition played a part in the game of conservative movements, whether it was the 19th-century conservatism of Pius IX or the American Protestant fundamentalists of the same period. Or, in our time, the American evangelicals and Russian orthodoxy. It is a reason to view theology as a church discipline with scepticism. Methodologically, there has been little evidence of the required distance from one’s own convictions to earn a place at the academy. At the same time, many theologians have been working as treasure hunters to create new approaches to traditional concepts.

Religious studies and its hesitations

The secular tradition of religious studies has brought us much and fortunately has not been bothered by a traditional licet or non licet. But it is also afraid to extend the conceptual aspect to the domain where people shape their own convictions. This even though postmodernism methodologically puts us on a different track than cherishing so-called objectivity. Without wanting to give up the search for truth. In short, in a weakened form, you also find the same contradictory forces within theology and religious studies. On the one hand conservatism, on the other innovation, but to a certain extent.

Opportunities for innovation

But that possibility for innovation does exist. Both within religious studies and theology. You would say, time to join forces and acquire our own place in the new field of forces as outlined above. Certainly, that need exists, but the spirit of the times is certainly not cooperating. The humanities are having an increasingly difficult time, and faculties of religious studies and theology are either being closed or reduced to minimal programs that function as a terminal construction. In my own country, the universities of Leiden and Utrecht decided to close the BA programs in minor languages such as French, German, Italian, Korean, religious studies, Hebrew, Persian, Arabic, Islamic studies, and Modern Middle Eastern studies. Have we as humanities, theology and religious studies, worked together enough? In the academic culture, French, for example, has become a rara avis and that applies a fortiori to Italian. So how do we, small disciplines within the humanities, maintain the innovative character? Or better said, how can we focus on it, discover it?

A call to action

That requires scolarly hard work. But also social and political cooperation. Within our own disciplines, the ability to leave the separation of theology and religious studies behind us. So on the one hand, taking more distance from church traditions, on the other hand, being less afraid to connect the domain of the conceptual with religious beliefs. Given the developments on the geopolitical level, we do not have much time and we could easily become an extinct species in the academic landscape, the dodo of the humanities. On the other hand, the role of religion, precisely on that geopolitical and economic level, will increase. So it will be hard work. EARS is very committed to that. Because the intention is not for twilight to herald the fall of night. But for it to make the stars and other dimensions visible.

Matthias Smalbrugge

Chair EARS