Normativity and Catholicism in a changing Irish landscape

Normativity and Catholicism in a changing Irish landscape

The Catholic Church’s influence in Irish society has weakened over the past decades. However, tensions over abortion, religious education, and LGBTQ+ rights are by no means resolved.

This article is part of our series on normativity in Europe.

The Catholic Church’s power in Ireland has shaped the country’s national identity. Columnist T.P. O’Mahony perfectly encapsulates this influence, stating that since the Republic’s creation, Catholicism has “run through the social fabric [of Ireland] like grain through wood.”[1] While Ireland is made of different religions and Christian denominations, the norm in Ireland has been defined by a predominantly Catholic identity, dictating the morals and ethics of the country.[2]

However, Ireland has not been immune to political and social changes that have occurred across Europe since the mid-20th century. Public debates over several issues have resulted in loosening the Catholic Church’s grip over the nation’s morality. Discussion of how Catholicism became the norm and shaped Irish society will now take place. Moreover, focus will be given to debates about abortion. This issue highlights the shifting understandings of morality and ethics and how these have caused deep rifts within the country that are yet to be resolved.

Catholicism and Irish identity

Under British colonial rule, the Catholic Church (henceforth referred to as the Church) was seen as a ‘protector’ of Irishness.[3] As the modern Republic was established in 1922, so was a symbolic dichotomy between Irishness-Catholicism and Britishness-Protestantism. The monolithic view was that Catholic values should be ‘the definers of Irish identity’ despite some citizens who identified as Protestant.[4]

In the Republic’s early years, the Church held the moral authority, allowing it to shape the political agenda and veto any policies that it believed to be ‘morally objectionable’.[5] While other European countries became more interconnected in the early part of the 20th century, ‘insular self-sufficiency’, this being a tendency to look inwards and limit trade with other countries, was the dominant objective in Ireland.[6] Foreign newspapers were taxed, and books and films were censored.[7] Therefore, until the mid-20th century, a traditional, inward-looking, and morally-driven Catholic framework shaped Ireland.

Shifting normativity

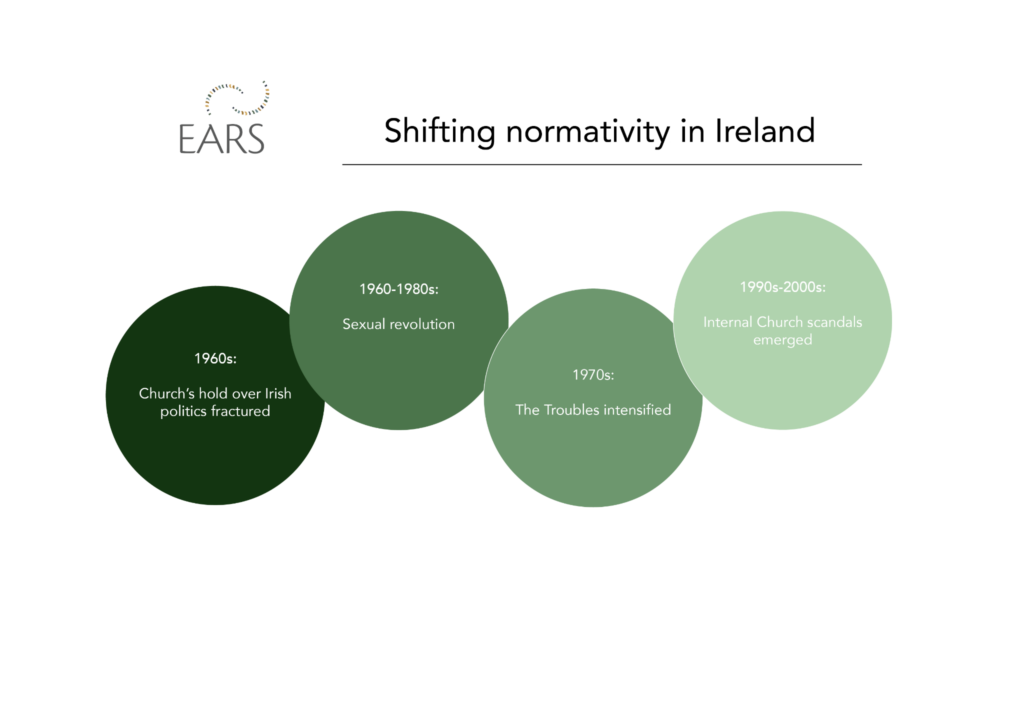

While for many Irish citizens, Catholicism “has been the social cement that provided cohesion and stability,” internal and external factors led to a shift in Catholic normativity from the mid-20th century onwards.[8] Firstly, in the 1960s, the Church’s hold over Irish politics ‘fractured’ and the State reformed some domains previously under church control.[9]

Secondly, The Troubles, which refers to a sectarian conflict between Unionists and Irish nationalists, began to intensify in the early 1970s.[10] While the conflict mostly took place in Northern Ireland, at times violence occurred in the Republic. The Troubles were not a religious conflict but they did have an impact on religiosity and Catholic morality in Ireland. Journalist Cahir O’Doherty speaks of how “the interminable conflict … impacted the spirit and spiritual life of the Irish over four decades.”[11] People witnessed not only the horrors of the conflict but also how “religion had fostered and hardened the attitudes” that led to the conflict.[12] By the time the Good Friday Peace Agreement was signed in 1998, Catholic affiliation had slightly declined,[13] suggesting that the experience of The Troubles may well have impacted both the religiosity of Irish citizens and their trust in the Church to bring peace.

Thirdly, internal scandals within the Church that emerged throughout the 1990s and 2000s ‘compounded the growing fragmentation of Irish-Catholic identity’.[14] Cases of sexual abuse by priests and illegal adoption organised by the Church led many Irish citizens to ‘ignore the Church’s guidance on social issues’.[15]

Alongside these internal factors, the sexual revolution that swept across Europe made a mark in Ireland and impacted the Church’s influence. Until this point, the Church had a monopoly on sexuality and women’s bodies. Yet, access to better information about sex and reproductive rights led many women to slowly turn away from the Church’s moral values and embrace more liberal teachings.[16] [17] With time, this trend grew and was reflected in major legal changes, including the 1979 law that allowed the importation and sale of contraceptives[18] and the 1996 law that removed the constitutional prohibition on divorce.[19]

The Church, politics, and women’s autonomy

No event better exemplifies the tensions between Irish society and the Church than the issue of abortion. As the sexual revolution heralded a new, liberal approach to women’s autonomy, the ‘reliance on religious doctrine to guide legislation’ was coming under pressure.[20] Therefore, the Church and political right turned to the issue of abortion and pushed for recognition of the equal right to life of the pregnant woman and the unborn to be written into law. They succeeded and the Eighth Constitutional Amendment was introduced in 1983.[21]

The Eighth Amendment referendum was highly divisive and faced opposition from some on the political left.[22] However, it highlighted that through much of the 1970s and 1980s, “the Church still exercised cultural influence among Irish citizens through … its ability to frame political debates on moral policy issues.”[23] Moreover, it reconfirmed the moral panic over the future of Ireland.[24]

Yet, over the next 38 years, the Church’s moral influence over political debates began to face even more criticism. When it came to abortion, many Irish citizens felt that their country remained inward-looking and out of touch with much of Europe.[25] Meanwhile, several high-profile cases of women who died because they were denied abortions appalled Irish citizens.[26] These reasons, among many others, led to the 2018 referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment. The Consitution of Ireland had previously prohibited abortion unless there was serious risk to the life of the mother[27] but this new amendment, which was voted in by 66.4% of Irish citizens, permitted parliament to legislate for abortion.[28]

Fundamental change?

The extended and intensely fierce debates on abortion reflect an Ireland struggling to come to terms with its changing landscape. The Thirty-Sixth Amendment highlighted how normativity in Ireland, which had once been defined by the influence of Catholic morality, has shifted. As the 2016 census revealed, religious affiliation has been declining overall, while those who identify as religious are increasingly not Catholic.[29] Therefore, the Church’s centuries-old influence in Irish society has inevitably weakened.

However, the tensions between the Church and some of Irish society over issues such as abortion, religious education, and LGBTQ+ rights are by no means resolved. The symbiotic relationship between the Church and politics is still in existence and support for the Church from many Irish citizens remains stable. Due to this, Catholic normativity may have shifted but it has not disappeared.

Our team of analysts conducts research on topics relating to religion and society. In the second half of 2021, we are focusing on the subject of normativity. Find out more on the EARS Dashboard.

Sources

[1] Ireland a “moral wasteland” due to decline of religion

[2] Morality in a Changing Irish Society

[3] Persistence and Change in Morality Policy: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Politics of Abortion in Ireland and Poland

[4] Debating Divorce: Moral Conflict in Ireland

[5] Persistence and Change in Morality Policy: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Politics of Abortion in Ireland and Poland

[6] Debating Divorce: Moral Conflict in Ireland

[7] Debating Divorce: Moral Conflict in Ireland

[8] Loss of faith leaving us in a moral wasteland

[9] Persistence and Change in Morality Policy: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Politics of Abortion in Ireland and Poland

[10] This sectarian conflict occurred between Unionists, who were mostly Ulster Protestants and wanted Northern Ireland to remain within the UK and Irish nationalists, who were mostly Irish Catholics and wanted Northern Ireland to leave the UK and join a united Ireland (the Troubles | Summary, Causes, & Facts)

[11] Ireland a “moral wasteland” due to decline of religion

[12] Ireland a “moral wasteland” due to decline of religion

[13] Papal visit: Ireland’s Catholic Church in graphs

[14] Persistence and Change in Morality Policy: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Politics of Abortion in Ireland and Poland

[15] After Scandals, Ireland Is No Longer ‘Most Catholic Country In The World’

[16] Ireland a “moral wasteland” due to decline of religion

[17] The Sexual Revolution in Ireland – 1970 Words | Research Paper Example

[18] Ireland allows sale of contraceptives – HISTORY

[19] Family Law (Divorce) Act, 1996 Permanent Page URL

[20] Understanding the transformed moral landscape in Ireland following the ‘repeal the 8th’ referendum

[21] What is the Eighth Amendment?

[22] Friday, December 10, 1982 – Page 15

[23] Persistence and Change in Morality Policy: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Politics of Abortion in Ireland and Poland

[24] Understanding the transformed moral landscape in Ireland following the ‘repeal the 8th’ referendum

[25] Majority support repeal of Eighth Amendment, poll shows

[26] Miss D and the Irish abortion debate

[27] Changes in the abortion legislation in Ireland: The Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 – Burrell – 2017 – BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology – Wiley Online Library

[28] Referendum results on the Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 2018 – data.gov.ie